Ethnic Minorities and Conflicts

Ethnic Minorities and Conflicts

According to the 2014 government census, Myanmar has a population of more than 51.4 million. It was the first census in over 30 years, and fell short of estimates of 60 million. Populations from certain northern zones of Rakhine State, home to the Rohingya minority, and some villages in the states of Kachin and Kayin were not counted.

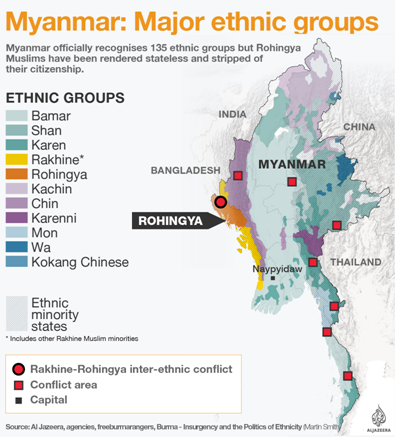

Myanmar contains (officially) 135 major ethnic groups and seven ethnic minority states, in addition to seven divisions populated mainly by the Burmese majority (also known as Bamar). More than 100 languages are spoken in Burma. Minority ethnic communities are estimated to make up at least one-third of the country’s total population and to inhabit half the land area. The main ethnic groups living in the seven ethnic minority states of Burma are the Karen, Shan, Mon, Chin, Kachin, Rakhine and Karenni. Other main groups include the Nagas, who live in north Burma and are estimated to number more than 100,000, constituting another complex family of Tibetan-Burmese language subgroups. Other ethnic groups with significant numbers include Pa-O, Wa, Kokang, Palaung, Akha, and Lahu.

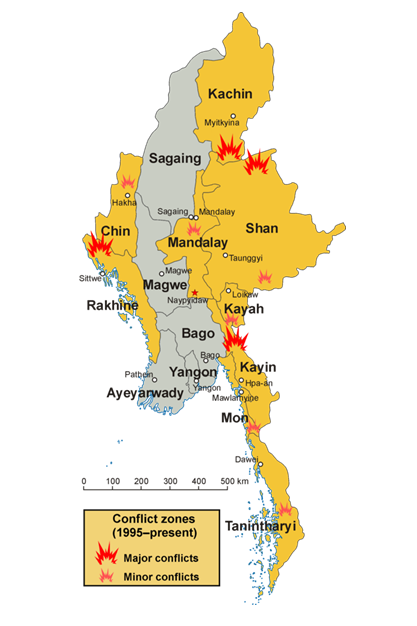

Conflict Zones

Conflicts Explained

Thai Border

1. Tanintharyi // Ethnic composition: Bamar, Karen, Mon, Shan, Rakhine

The largest ethnic armed group in the area is the Karen National Union (KNU). The KNU has had minor conflicts with the government, and have previously had control over small regions that have been retained by the government (according to the Thai NGO The Border Consortium). Some other small armed groups operate in the state; however the impact of these is not massive.

2. Mon// Ethnic composition: Mon, ethnic Bamar, Kayin and Pa-O ethnic groups, others

The main armed actor in Mon areas is the New Mon State Party (NMSP). It has held a ceasefire since 1995, and governs two autonomous territories that are home to tens of thousands of Mon civilians. A number of small NMSP splinter factions are in conflict with the government. Karen National Union (KNU) also has presence in the state. The two organizations have districts that overlap considerably.

Mon/Kayin border conflict: NSMP exercise less autonomy in this area. Here, its relations with local communities are tolerated by the government. Communities in such areas will typically have to manage relations with the NMSP, government, and in some cases Karen armed actors too.

3. Kayin // Ethnic composition: Karen

The biggest opposition groups Karen National Union (KNU) and the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA)

Conflict between government and Karen. Government has denied claims of ethnic cleansing put forth by the DLA Piper to the UNSC.

Conflict: One of the most conflicted areas because of the amount of non-state actors and overlapping. Since the ceasefires in 2011 and 2012, areas influenced by Karen armed actors have seen increasing expansion of government administration. Nine “sub-townships” in Kayin State have attracted the bulk of the state’s international aid since the ceasefires, and have been earmarked as potential return sites for displaced persons. In the central settlements in each of these areas, buildings and new roads have been built. Meanwhile, communities in surrounding areas remain governed primarily by ethnic armed groups, and have much less interaction with the state government. Government expansion has been of major concern among some powerful military factions of the KNU, leading to considerable scepticism about the entire peace process. General Baw Kyaw Heh, whose troops have long maintained KNU control across much of Hpapun Township, has lamented that in lieu of comprehensive ceasefire terms.

4. Kayah// Ethnic composition: Kayah, Bamar, Shan, Karen

Rural parts of Kayah state are contested by a number of ethnic armed actors, with the most prominent and politically active being the Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP). Many areas have some sort of agreement between government authorities and the armed groups on administrative affairs. In the mining hub of Mawchi, numerous armed actors contest the area.

South East conflict: Following nearly seven decades of ethnic armed conflict, new ceasefires in Karen areas of the southeast remain fragile, as do the territorial arrangements resting on them. All across the southeast, communities remain subject to multiple authorities with parallel systems of governance of varying degrees of formality. Local communities are burdened with multiple tax regimes and a difficulty managing relations with rival armed actors.

5. Mandalay// Ethnic composition: Bamar, Chinese, Yunnan, Indians, Anglo-Burmese, Shan

Conflict: (none appear to be discussed recently. In 2014, people feared a sectarian conflict between Muslims and Buddhists)

Bangladesh/India Border

6. Chin State// Ethnic composition: Chin

Minor conflicts: In Chin State, following years of mobile guerrilla warfare, the Chin National Front (CNF) and government agreed through state-level and Union-level ceasefires that the armed group could establish bases and ‘move freely and without hindrance’ in ‘Tlangpi, Dawn and Zangtlang Village Tracts of Thantlang Township, and Zampi and Bukphir Village Tracts of Tedim Township’. According to the organization and other observers, the CNF enjoys a level of autonomy in these areas. The Arakan Liberation Party (Rakhine Buddhists) has limited presence in Chin. Since March 2015, another Arakan nationalist armed group has established at least a guerilla presence in some townships and has begun interacting with populations.

7. Rakhine State// Ethnic composition: Rakhine (Buddhist), Rohingya (Muslim), Chin.

Conflict: There is ongoing religious violence between Rohingyas and Rakhines. Rohingyas constitute 80-96% of the population near the border with Bangladesh and the coastal areas.

- 2012: The Rakhine state riots were a series of conflicts between Rohingya muslims and ethnic Rakhines. Buddhist Rakhines feared they would become a minority in their ancestral state. From both sides, whole villages were decimated. Rohingya NGOs overseas have accused the Burmese army and police of targeting Rohingya muslims through arrests and participating in violence. In july 2012, the Burmese Government did not include Rohingya minority groups in the census, but rather classified them as stateless Bengali Muslims since 1982.

- 2016 onwards: Rohingya persecution in Myanmar. It is an ongoing military crackdown by the government army and police on Rohingyas in Rakhine. The crackdown by the government was a response to attacks on Myanmar border posts in October 2016 by Rohingya insurgents. The Government army has been accused of wide-scale human rights violations, including extrajudicial killings, gang rapes, arson and infanticides.

Chinese Border

8. Kachin State// Ethnic composition: Kachin, Shan, small number of Tibetans

Conflict: Since 2011, there has been near continuous armed conflict between the government and the armed wing of the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). The most dramatic changes to the governance environment have been two fold. First, there has been the displacement of approximately 90,000 people from over 100 villages, about 70,000 of whom fled deeper into KIO territory. Second, there has been a marked decrease in areas firmly controlled by the organization, as the Tatmadaw has moved dozens more infantry and support battalions into the area. Nonetheless, the KIO administration system has persisted in many parts of its old territories, particularly in its stronghold in southeastern Kachin, but also elsewhere in the state such as in Hpakan and Tanai Townships.

9. Shan State // Ethnic composition: Shan, Bamar, Han-Chinese, Karens, Wa, Ta’ang, Lisu, Jinghpaw

The three main armed actors in Shan, the OPa-O National Organization (PNO), Restoration Council Shan State (RCSS) and Pa-O National Liberation Organization (PNLO), demonstrate the sheer variety among the governance roles played by ethnic armed actors, and the inevitable unsustainability of the present ad hoc territorial arrangements.

The PNO winning of all seats in the Pa-O SAZ has provided a new platform for working in an official government capacity, but the extent of its influence remains largely dependent on the informal administration role of its powerful People’s Militia Force, the PNA. In contrast, the RCSS was borne out of pre-existing rebel movements, and through insurgency, has expanded quickly in recent years to establish its independent administration system in rural areas throughout Shan State. Skirmishes between the group and the Tatmadaw have decreased significantly since 2013, but they still take place, and escalation of conflict remains a continuous threat, given the lack of clear agreements between the two sides.

The PNLO has been able to secure a degree of autonomy over a number of rural village tracts and financial support for roads and other development. However, these agreements have been contested by the RCSS, which also claims parts of these territories, leading to fresh armed conflict in 2015.

North-Western conflicts: Since 2011, there has been near continuous armed conflict between the government and the armed wing of the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). The most dramatic changes to the governance environment have been two fold. First, there has been the displacement of approximately 90,000 people from over 100 villages, about 70,000 of whom fled deeper into KIO territory. Second, there has been a marked decrease in areas firmly controlled by the organization, as the Tatmadaw has moved dozens more infantry and support battalions into the area. Nonetheless, the KIO administration system has persisted in many parts of its old territories, particularly in its stronghold in southeastern Kachin, but also elsewhere in the state such as in Hpakan and Tanai Townships.

North Conflict: in 2010, the Shan State Progressive Party/Shan State Army (SSPP/SSA) split as its 3rd and 7th brigades agreed to form a PMF and the most powerful, the 1st brigade, refused. Fighting then recommenced between the Tatmadaw and the rebel 1st Brigade.

Myanmar border & relationship with neighboring Countries

CHINA: Problematic relations due to recent ongoing conflicts with ethnic Chinese rebels and Tatmadaw near the border, as well as Burmese recent hostilities against Chinese. However, China is very willing to continue playing a constructive role during the internal conflicts. In March 2017, 20,000 people from Myanmar have flooded into border camps in China, seeking refuge. China is providing humanitarian assistance while taking steps to ensure peace and tranquility in the border region.

2015: fighters of the predominantly ethnic Chinese MNDAA launched a predawn raid on police, military and government sites in Laukkai, the capital of the northeastern Kokang region. The MNDAA is a part of the Northern Alliance coalition othe Kachin Independence Army. Many died and tens of thousands fled during that fighting, which also spilled into China and led to the death of five Chinese citizens, angering Beijing.[2]

2017: Clashes between Myanmar military and ethnic Chinese rebels in the Kokang region have created a situation of panic among border residents

2017: China endorses Myanmar’s offensive against Rohingya Muslim insurgents – although this has caused nearly 400,000 people to flee to Bangladesh (ethnic cleansing claims).[3]

BANGLADESH: The Relations between Bangladesh and Myanmar have been strained by the Rohingya refugee crisis. 2017: Allegations: Myanmar laying landmines across a section of its border with Bangladesh. The purpose may be to prevent the return of Rohingya Muslims fleeing violence.

* Bangladesh has accused Myanmar of repeatedly violating its air space, and warned that any more “provocative acts” could have “unwarranted consequences”. [4]

* Bangladesh border guards say Myanmar troops fired mortars and machine guns at Rohingya civilians (mostly women and children) trying to cross the border into Bangladesh. At the border, Bangladesh has a “zero tolerance policy – no once will be allowed”.[5] Bangladeshi officials regularly advocate a tough approach to refugees in official interview but tend to let them through.

THAILAND: The relations with Myanmar focus mainly on economic issues and trade, but sporadic conflicts occur due to the alignment of the border and the stream of refugees.

* The 2010–2012 Myanmar border clashes: skirmishes between the Tatmadaw and the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army. The clashes erupted along the border with Thailand shortly after the general election on 7 November 2010. An estimated 10,000 refugees have fled into nearby neighboring Thailand to escape the violent conflict.[6]

* Nine refugee camps have been in place on the Thai border since mid-1980s. This year Thailand, working together with the UN, seek to repatriate close to 100,000 refugees.[7]

INDIA: 20 Sep 2017: New Dehli wants to deport 40,000 [all] Rohingya Muslims currently residing in India amid concerns of terror threats and the potential destabilization of ally Bangladesh.[8]

[1] https://asiafoundation.org/resources/pdfs/ConflictTerritorialAdministrationfullreportENG.pdf

[2] www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/2077476/more-20000-flee-myanmar-conflict-and-cross-border-china

[3] https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2017/09/14/asia-pacific/china-endorses-myanmars-crackdown-u-n-sees-ethnic-cleansing/#.WcpdT8Zx2Uk

[4] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-rohingya/bangladesh-warns-myanmar-over-border-amid-refugee-crisis-idUSKCN1BR03V

[5] http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/08/myanmar-violence-traps-rohingya-bangladesh-border-170826101215439.html

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2010%E2%80%9312_Myanmar_border_clashes

[7] https://www.voanews.com/a/myanmar-refugees-thai-camps-repatriation-challenges/3847329.html